| CAT# | Product Name | M.W | Molecular Formula | Inquiry |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A03001 | (Des-His6)-ACTH (1-24) (human, bovine, rat) | 2796.34 | C130H203N37O30S | |

| A03002 | (Des-Ser3)-ACTH (1-24) (human, bovine, rat) | 2846.40 | C133H205N39O29S | |

| A03006 | (Tyr15)-ACTH (7-15) | 1109.3 | C55H76N14O11 | |

| A03007 | [Glu10]-ACTH (1-17) | 2165.5 | ||

| A03010 | Acetyl-ACTH (1-14) | 1722.95 | C79H111N21O21S | |

| A03011 | Acetyl-ACTH (2-24) (human, bovine, rat) | 2888.44 | C135H207N39O30S | |

| A03012 | Acetyl-ACTH (3-24) (human, bovine, rat) | 2725.26 | C126H198N38O28S | |

| A03013 | Acetyl-ACTH (4-24) (human, bovine, rat) | 2638.19 | C123H193N37O26S | |

| A03014 | Acetyl-ACTH (7-24) (human, bovine, rat) | 2240.73 | C107H170N32O21 | |

| A03015 | ACTH (1-10) | 1299.4 | ||

| A03019 | ACTH (1-16), human | 1937.3 | C89H133N25O22S1 | |

| A03021 | ACTH (12-39), rat | 3173.9 | C145H227N39O41 | |

| A03022 | ACTH (1-24), human | 2933.5 | ||

| A03023 | ACTH (1-39) (mouse, rat) | 4582.23 | C210H315N57O57S | |

| A03024 | ACTH (1-39), guinea pig | 4529.2 | C206H308N56O58S | |

| A03025 | ACTH (1-39), human | 4541 | C207H308N56O58S | |

| A03026 | ACTH (1-4) | 486.5 | ||

| A03029 | ACTH (2-24) (human, bovine, rat) | 2846.40 | C133H205N39O29S | |

| A03030 | ACTH (3-24) (human, bovine, rat) | 2683.23 | C124H196N38O27S | |

| A03033 | ACTH (5-10) | 831.9 |

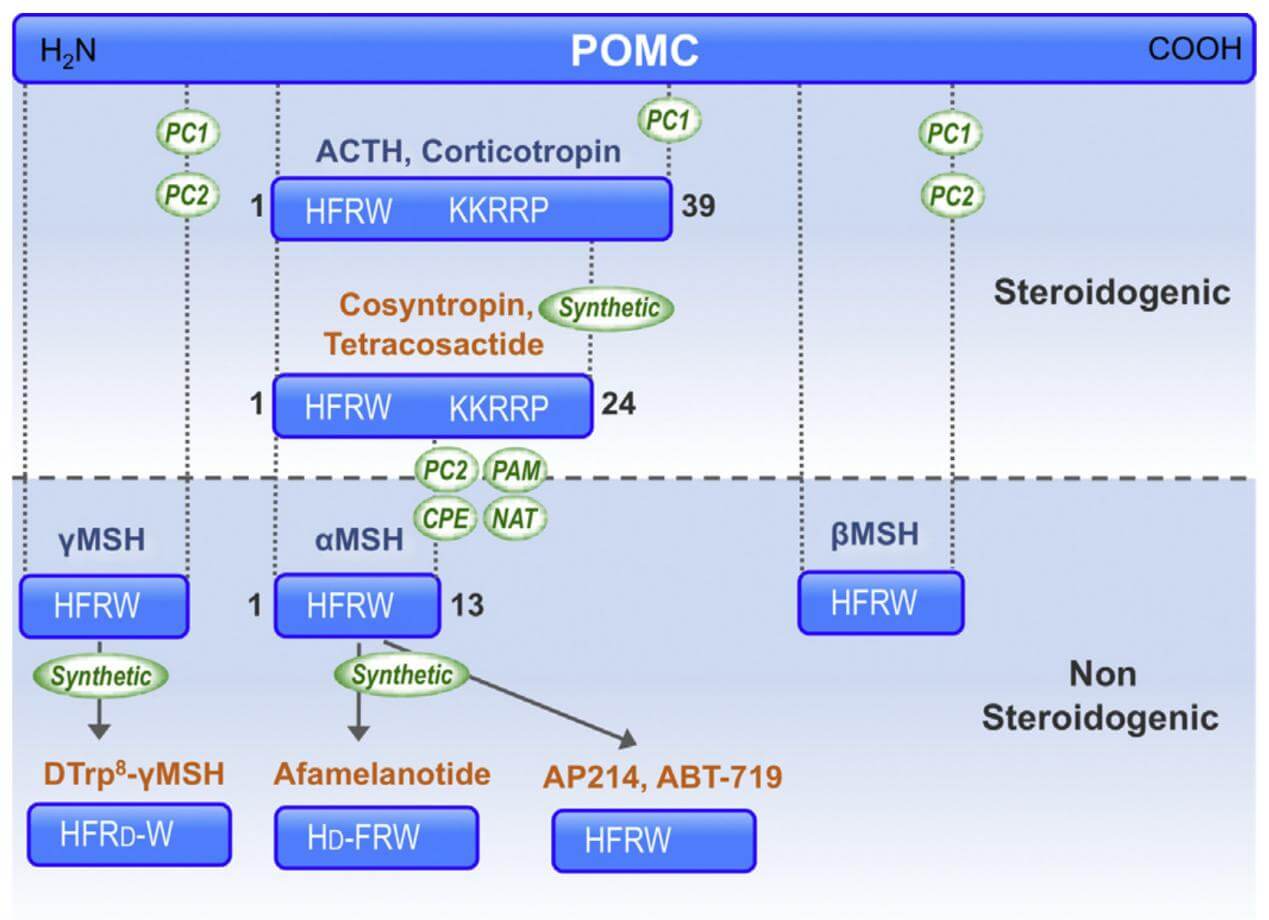

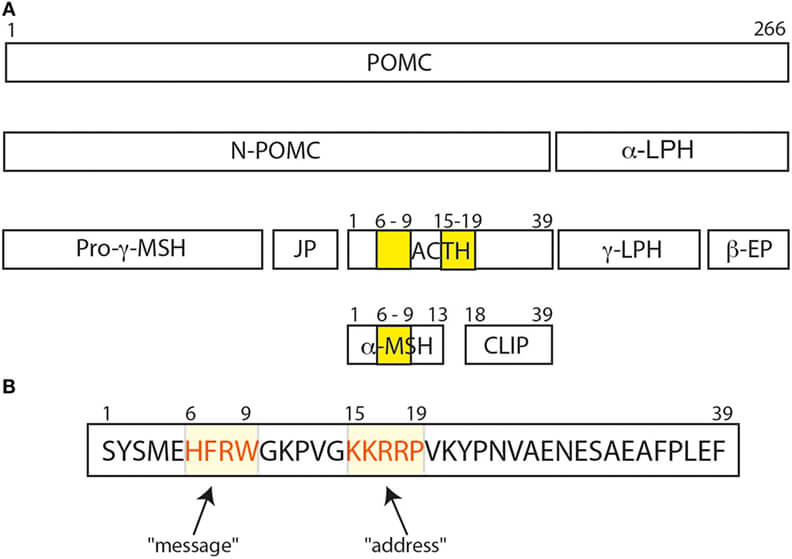

Twenty years after its initial description in 1933, the polypeptide hormone known as adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) was shown to increase adrenocortical activity. Pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC), the sole precursor to ACTH, is primarily synthesized in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus and the corticotroph and melanotroph cells of the anterior and intermediate lobes of the pituitary gland. Other organs, such the skin, have also been found to synthesize ACTH. Following its synthesis and folding, POMC undergoes processing in secretory granules and transportation in vesicles before finally arriving at the plasma membrane. Due to a highly conserved sorting signal motif, the controlled secretory pathway is followed by cell-specific hormones like POMC and their timing of secretion, which is determined by the selective cleavage of POMC by prohormone convertase (PC). Immature secretory granules digest POMC with the help of PC1/3 and PC2 enzymes. The posttranslational cleavage that produces 16-kDa N-POMC, ACTH, and β-lipotropin occurs in the anterior pituitary lobe and is carried out by PC1/3. Peptides like α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone and β-endorphin are produced by a more intricate processing of POMC in the hypothalamus and intermediate pituitary lobe, which involves PC2 activity and other enzymes.

The mature granules in the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland release ACTH into the bloodstream after PC1/3 cleaves it from POMC. ACTH binds to the melanocortin 2 receptor (MC2R) on peripheral cells. Some melanocortin receptors (MCRs) can bind to peptides produced from POMC and ACTH, including the highly selective MC2R. Other MCRs include MCR1, MCR3, MCR4, and MCR5. A rise in intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) stimulates the protein kinase A (PKA) signaling pathway upon activation of MC2R, as it does with other GPCRs. The cAMP response element-binding protein and mitogen-activated protein kinase are two other intracellular pathways that ACTH activates. Although their autonomy from the PKA route is still up for debate, numerous additional secondary messengers are engaged in ACTH downstream signaling, and a role of calcium influx that collaborates with ACTH-mediated steroid production has also been discovered. In the adrenal glands, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) and other genes involved in steroidogenesis are transcribed when MC2R and ACTH interact.

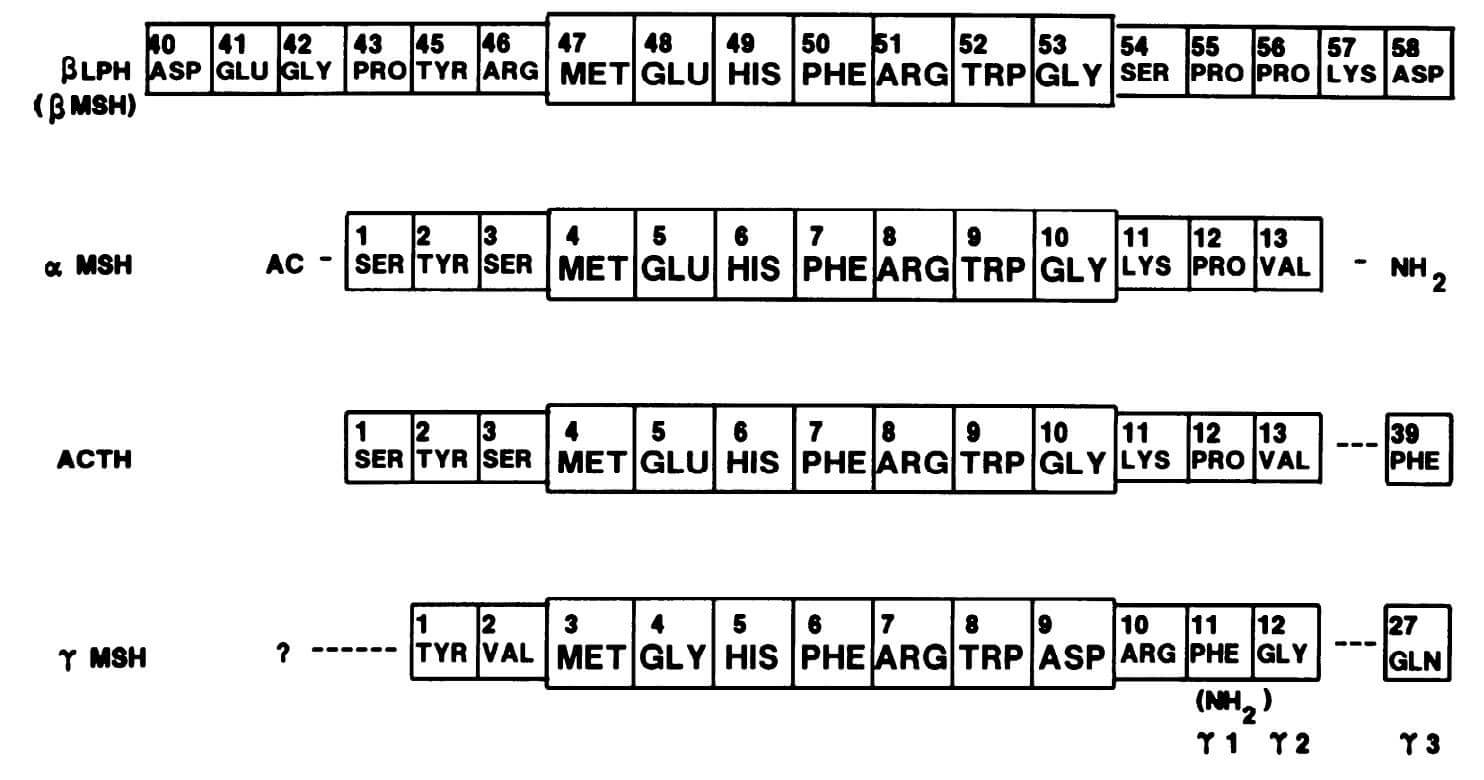

The nomenclature of the natural melanocortin peptides. (Montero-Melendez T., 2015)

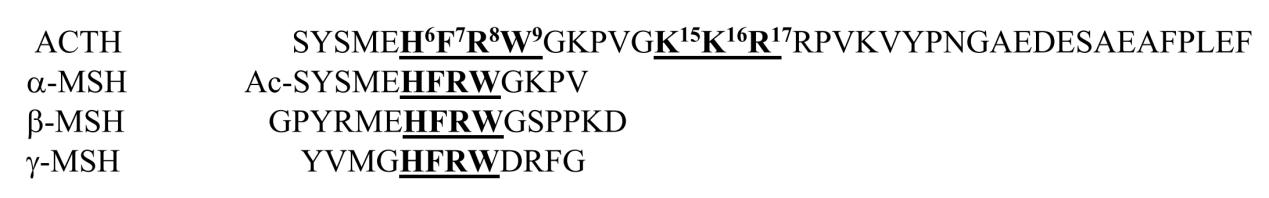

The linear non-atriacontapeptide ACTH, composed of a 39-amino acid (ACTH1-39), has species variations in the COOH terminal two-third of the molecule. First, there was still lacking a study of the ACTH crystal structure. Early in the 1970s, several polypeptides were extracted from several lobes of the vertebrate pituitary. Lowry found that although having different purposes, ACTH and β-lipotropin (β-LPH) have the identical amino acid motif H6F7R8W9.

ACTH's biological activity resides in the sequence of its first 24 N-terminal amino acid residues, and this sequence is identical in all species that have been studied. The same 24-amino acid sequence is available in synthetic form (Synacthen, Tetra-Cosactryn, or Cortrosyn) and is widely used in clinical practice. Minor changes in this sequence may have profound effects; for example, oxidation of the methionine at position 4 can cause a marked reduction in activity. The C-terminal part of the ACTH molecule varies in beef, sheep, pig, and human at residues 31 and 33. Human corticotropin has been completely synthesized, and several analogs have been prepared which have higher biological activity than the natural hormone, probably because of their relative resistance to peptidase cleavage and longer circulating half-life.

ACTH is derived from a substantial glycoprotein precursor, pro-adreno-corticotropin-endorphin, whose nucleotide sequence has been elucidated in the pituitary gland. Proteolytic cleavage produces β-lipotropin consisting of 91 amino acid residues and an ACTH precursor, which is then cleaved to generate ACTH and a bigger fragment known as the 16K fragment. The heptapeptide sequence, -Met-Glu-His-Phe-Arg-Trp-Gly-, is present at residues 4-10 of ACTH and at residues 46-52 of β-lipotropin. A portion of β-lipotropin is cleaved to generate γ-lipotropin (residues 1-58), β-endorphin (residues 61-91), γ-endorphin (residues 61-77), α-endorphin (residues 61-76), and metenkephalin (residues 61-65).

Amino acid sequences of ACTH. (Yang Y., et al., 2020)

The POMC protein and its various peptide cleavage products. (Ghaddhab C., et al., 2017)

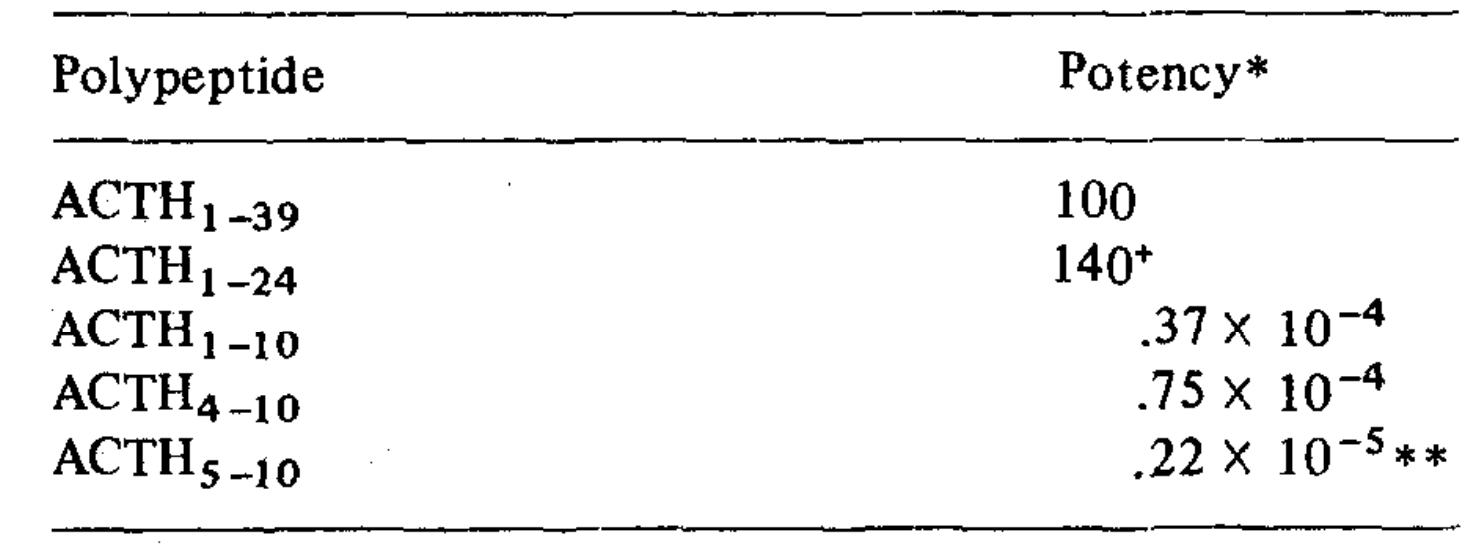

ACTH is a polypeptide composed of 39 amino acids (ACTH1-39) that binds to and activates its specific receptor, melanocortin receptor 2 (MC2R), via the two regions H6F7R8W9 and K15K16R17R18P19. Various research teams evaluated the biological activity of C-terminally shortened analogs of ACTH (1–39) using distinct bioassay techniques.

Molar potencies of ACTH polypeptides assayed by steroidogenesis. (Schwyzer R., et al., 1971)

ACTH(1-39) and ACTH(1-24) have about the same potency and exhibit the same Bmax when added to suspensions of isolated adrenal cells. Adrenocortical steroid production is stimulated in normal people by intranasal (IN) injection of ACTH(1-24). One study compared the levels of serum cortisol, aldosterone, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine following intramuscular (IM) and intravenous (IV) administration of 250 μg ACTH(1-24) in seven healthy adult males to find out how efficiently ACTH is absorbed into the adrenal medulla. Blood samples were taken 0, 30, 60, and 120 minutes following ACTH(1-24) injection. Administering ACTH intravenously or intramuscularly did not cause any adverse effects. Analogous to the earlier research, blood cortisol and aldosterone levels rose following intramuscular administration of ACTH(1-24), reaching a maximum 30 minutes following administration. The levels of epinephrine rose by 41.9% ± 13.1% and 63.3% ± 11.8%, respectively, sixty minutes after intravenous (IV) ACTH injection and stayed high throughout the sample period. Plasma norepinephrine levels rose by 55.9 ± 13.4% and 73.7 ± 15.0%, respectively, thirty minutes after intravenous (IV) or intramuscular (IM) administration of ACTH(1-24). These levels peaked 30 minutes after ACTH(1-24) administration and returned to baseline within 60 minutes. There was no change in plasma dopamine levels following intravenous injection of ACTH(1-24). The levels of catecholamines and adrenocortical steroids did not rise following intramuscular saline treatment. These findings prove that ACTH(1-24), when administered intravenously, increases the release of epinephrine and norepinephrine in addition to adrenocortical hormones.

Intravenous (iv) ACTH-(4–10) was shown to have pressor, cardioaccelerator, and natriuretic effects after research into the cardiovascular effects of peripheral administration of peptide sequences generated from adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) led to their identification. Pharmacological investigations in rats using beta- and alpha-adrenergic receptor antagonists suggested that catecholamine release mediated the cardiovascular effects of this peptide. Similar to ACTH-(4-10), gamma-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (gamma-MSH) has natriuretic and cardiovascular effects that are 1,000 times stronger than ACTH-(4-10). Rather than circulating vasopressin or angiotensin II, the pressor impact of intravenous gamma-MSH peptides seems to be reliant on preganglionic sympathetic drive maintenance. To express the complete pressor action of circulating gamma-MSH, however, central vasopressinergic (and maybe angiotensinergic) pathways must be present. Experiments with central lesion and a comparison of intracarotid and intrajugular infusions provided further evidence that the CNS may play a significant role in these cardiovascular effects. The cardiovascular effects of ACTH-(4-10) or gamma-MSH, according to structure-activity studies, are reliant on an Arg-hydrophobic amino acid sequence that is either COOH-terminal or close by it. Cardiovascular effects in rats mimic those of ACTH-(4-10) or gamma-MSH, and molluscan cardioexcitatory peptides share this need for biological activity. This provides more evidence that gamma-MSH peptides are similar to, if not the physiological counterparts of, a family of peptides known as cardioexcitatory peptides in birds and mollusks. Peptides produced from the NH2-terminal of pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) have been discovered to be elevated in the bloodstream in cases of psychological stress, cardiovascular illness, and bleeding. All of these states have an increase in central sympathetic drive. In the arcuate and nucleus commissuralis of rats, gamma-MSH peptides have been identified as localizing to POMC neurons. Vasomotor centers in the hindbrain are innervated by projections from the later nucleus. Administering gamma-MSH intraventricularly causes a sustained rise in mean arterial pressure. It is hypothesized that gamma-MSH peptides play a significant role as neurotransmitters in the central regulation of the cardiovascular system and may serve as a bridge between humoral and neurogenic pathways in this regulation.

Structures of POMC-derived peptides containing ACTH-(4-10). (Gruber K A., et al., 1989)

POMC is converted into a famous family of peptides by means of several cleavages. This family includes ACTH (1-39) and two of its derivatives, α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH) and corticotropin-like intermediate lobe peptide (CLIP or ACTH 18-39). In the raphe dorsalis (nRD), immobilization stress (IS) initially causes a rise in CLIP. This rise may determine the SWS and PS rebound induction, as the nRD includes sleep-promoting components. As is typical in such a case, patients' blood levels of corticosterone and CLIP/ACTH1-39 total immunoreactivity have changed, which is evidence that the IS has been effective. Lastly, the restoration processes that are needed to correct for the stress overshoot can include the rise in CLIP that happens in the arcuate (AN) four hours following the end of the restraint. The rat corticotropin-like intermediate lobe peptide ACTH (18-39) and its facilitative influence on paradoxical sleep.

Changes in ACTH and glucocorticoids levels during the day are known to affect the expression of genes involved in the regulation of the body clock. The dysregulation of the clock machinery in adrenal tumors leads to an increase in the production of corticosteroids, which is both greater and more arrhythmic. This suggests that hypercortisolism influences circadian genes, exacerbating disease-related complications. Keeping cells in a state of homeostasis requires precise synchronization of clocks to coordinate both internal and exterior impulses. When administered at a more natural interval by glucocorticoids, circadian gene expression normalizes in adrenal insufficiency patients.

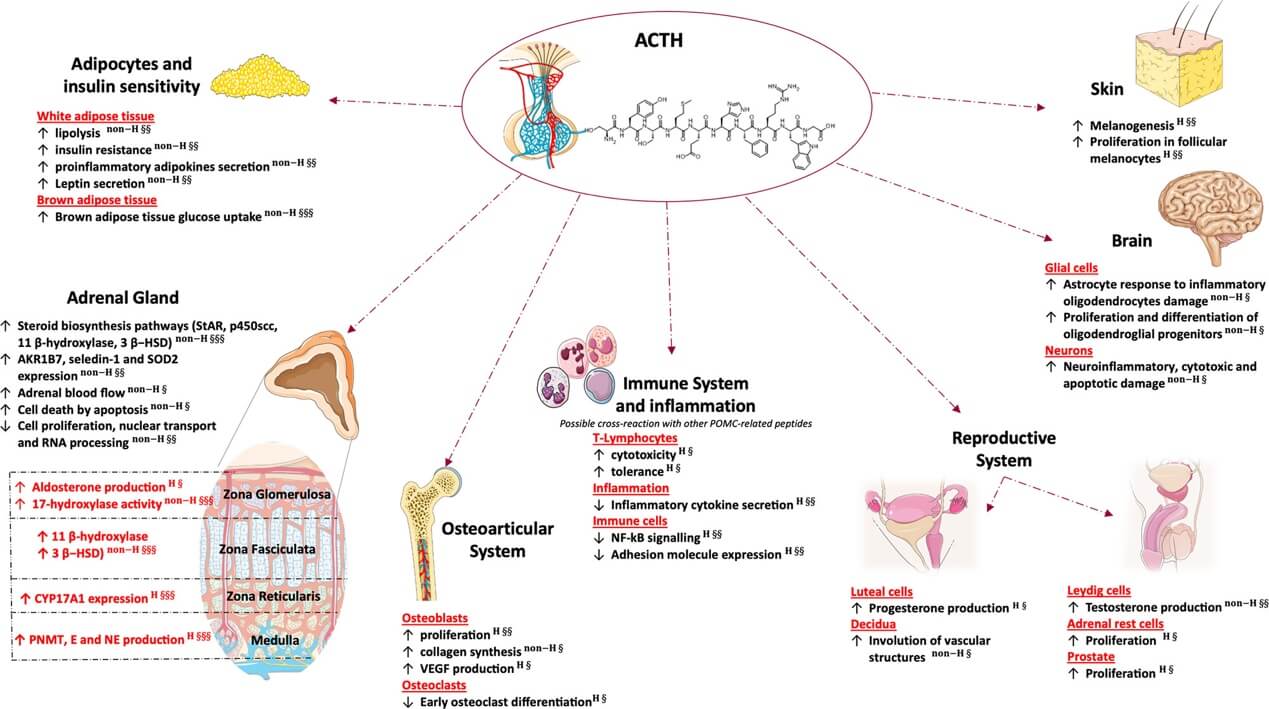

Short-term and long-term reactions are induced by ACTH, the primary hormone regulating adrenal steroidogenesis. Cholesterol mobilization occurs as a result of an increase in StAR gene transcription brought about by acute and chronic ACTH stimulation, the first substrate for the steroidogenic pathway. The first and last stage of steroidogenesis, the conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone, is catalyzed by StAR. Chronic stimulation of ACTH can also activate other steroidogenic enzymes, such as P450scc, an enzyme that converts cholesterol to pregnenolone within the mitochondria, and P450C11, an enzyme that converts deoxycorticosterone to corticosterone and 11-deoxycortisol to cortisol. Androstenedione, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and its sulphated derivative DHEAS are androgen precursors that are secreted by ACTH via CYP17A1. In addition, persistent ACTH injection causes the adrenal glands to enlarge, which may be due to an increase in steroidogenesis. Despite the fact that the idea that ACTH is not involved in aldosterone synthesis is now considered obsolete, ACTH primarily regulates the release of cortisol and androgen precursors under physiological settings. Even at normal dosages, ACTH may increase aldosterone synthesis by a modest but continuous Ca2+ influx because binding to MC2R also stimulates aldosterone production in addition to cortisol. Second messengers (cAMP and Ca2+ influx) are really produced when ACTH binds to MC2R. This mechanism improves steroid secretion via positive feedback loops. The effects of ACTH on aldosterone production may vary depending on the exposure. For example, aldosterone levels rise with continuous intravenous ACTH infusion but fall to baseline within 72 hours. In contrast, aldosterone levels stay high with pulsatile ACTH administration, which simulates its physiological release. Animal studies show that Angiotensin II signaling inhibits the activation of cAMP and Ca2+ intracellular cascades, which are activated by ACTH binding to MC2R, thus dampening the in vivo effects on mineralocorticoid secretion. On the other hand, the majority of findings on strong aldosterone activation by ACTH have been derived from in vitro research.

Lipid peroxidation and the production of reactive aldehyde metabolites are two steps in ACTH-induced steroidogenesis that lead to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and substantial cellular oxidative stress. Therefore, numerous enzymes involved in detoxification are mobilized by adrenal cells. This detoxification mechanism is influenced by ACTH, which regulates the production of aldo-keto reductases. Also, 24-dehydrocholesterol reductase, or seladin-1, is produced and nuclear redistribution is induced in human and rat adrenal cells by ACTH treatment. The metalloenzyme SOD2 is involved in the scavenging of mitochondrial ROS, and ACTH also increases its synthesis. Therefore, ACTH regulates the synthesis of both steroidogenic and nonsteroidogenic enzymes, the latter of which protects cells from ROS-induced toxicity.

According to an in vitro research, ACTH increases cell death via apoptosis of isolated cells in adrenal cortex cultures, even though zona glomerulosa is more vulnerable to ACTH's cytotoxic and antimitogenic actions. Contrarily, these effects are more pronounced in the zona fasciculata and zona reticularis. This contradicts the results of animal research showing that ACTH enhances adrenal blood flow and modulates adrenal gland trophicity. Also, the vascular network regresses because glucocorticoid-induced reduction of ACTH causes vascular alterations via reducing protein production of vascular endothelial growth factor. In addition to lowering adrenal weight and cellularity, it inhibits cell growth and promotes apoptosis. Furthermore, there is an increase in MC2R expression in the undifferentiated zone, a stem cell-rich area, and significant zona fasciculata atrophy in mice deficient in the MC2R gene. offers evidence that ACTH may play a key role in the differentiation of adrenal cells and that the ACTH-MC2R complex is essential for the maturation of the adrenal glands. Apoptosis models in vitro and in vivo don't agree, and this is because to intraglandular variables including vascularization and autonomic innervation. This suggests that ACTH is primarily a differentiation factor that controls steroid release and not a proliferative one, which supports the idea that the structural integrity and compartmentalization of the adrenal gland are important.

In addition to its well-known effect on the adrenal cortex, certain studies have shown that ACTH may also influence the adrenal medulla. After hypophysectomy, rats have lower levels of adrenal epinephrine and the enzyme phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT), which converts norepinephrine to epinephrine. These modifications came back after the ACTH injection. Chronic ACTH treatment raises PNMT even in healthy rats, suggesting that ACTH-induced stimulation may influence the enzyme activities of the adrenal medulla. Both epinephrine and norepinephrine were discovered to be higher in the adrenal venous blood of individuals after an ACTH stimulation test. This is because ACTH increases blood flow and enzyme activity. It is possible that ACTH facilitates these processes by increasing the exposure of the adrenal medulla to glucocorticoids, which are potent inducers of PNMT.

In the past, when glucocorticoid levels were higher, ACTH activity had a deleterious effect on bone mass, causing osteoporosis and bone loss. Cortisol does not seem to have any detrimental effect on bone differentiation or proliferation at normal levels; nevertheless, this is only the case when there is an excess of endogenous or exogenous glucocorticoids. In contrast to patients without Cushing's disease, people with adrenal Cushing's syndrome seem to be more likely to suffer from osteoporosis, since they often have ACTH suppression. While these effects are caused by a drop in adrenal androgens, which is caused by low ACTH levels, ACTH may also have a protective effect on bone. Osteoblasts express ACTH receptors that are highly affinity-bound. Furthermore, high-dose ACTH enhances osteoblastic proliferation, which in turn increases collagen formation by osteoblasts. It seems, however, that lowering the amount of ACTH inhibits osteoblast differentiation. Osteoblast VEFG production is promoted by ACTH in vitro, but osteoclast differentiation is inhibited. There may be a function for locally generated ACTH in controlling bone metabolism, given that mouse osteoclasts can produce and release ACTH. Finally, ACTH injection is included as a possible therapy option in gout care recommendations. This is because the hormone has a direct role in glucocorticoid production and there is a concept that it may have a therapeutic impact on illnesses involving inflammation of the joints.

For males: In fetal testis gonocytes and Leydig cells from mice, the MC2R receptor is present. A dose-dependent increase in testosterone production is seen in fetal and neonatal mice, suggesting that the testis MC2Rs are functionally active, even if the effect is eliminated in postpubertal animals. Accordingly, ACTH may regulate testosterone synthesis in the developing testes, but not in adults. The adrenal disorders section will investigate how testicular adrenal rest tumors (TART) arise in cases characterized by early exposure to high levels of ACTH. Very little is understood about the prostate. The process by which prostate-activated MC2R enhances cell proliferation seems to be concentration dependent. Therefore, inhibiting MC2R signaling has emerged as a novel strategy for the treatment of prostate cancer. Interestingly, after receiving a local injection of ACTH(1-24) into the hypothalamic periventricular area, male rats were able to generate penile erections via the melanocortin-3 receptor.

For females: In a clinical trial, four out of nine female premenopausal Addison's disease patients had menstruation abnormalities after being administered substantial doses of tetracosactide (ACTH1-24). The observation that MC2R expression was higher in the glandular epithelium and lower in the stromal cells of human endometrium provided evidence for a direct function of ACTH in regulating secretion from the endometrial glands. In cultured decidua, large dosages of ACTH1-24 also stimulate involution of vascular systems. It was previously thought that ACTH directly influences ovarian steroidogenesis, as MC2R is also expressed in rabbit and cow ovaries. Research involving people is lacking, despite promising results in animal models from in vitro trials. According to clinical trial results, dysregulated adrenal steroidogenesis may play a role in the pathogenesis of hyperandrogenism in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), which has centered on research on the effects of ACTH on androgen production in PCOS.

Glucocorticoid independent effects of adrenal and extra-adrenal ACTH. (Hasenmajer V., et al., 2021)

The adrenal glands are the final destination for ACTH after it has been produced; there, it binds to MC2R in the fasciculate zone of the gland cortex. When ACTH binds to MC2R, it activates protein kinase A, which in turn triggers gene transcription that is involved in the generation of glucocorticoids. Adrenocortical steroidogenic cells produce two active forms of this hormone, cortisol and corticosterone, by a series of biochemical steps facilitated by cytochrome P450 enzymes. Cholesterol is the starting material for this process. While corticosterone is the most abundant glucocorticoid in rats, the most important glucocorticoid in humans is cortisol, also known as hydrocortisone. The two hormones have identical effects on the body, including controlling metabolism, immunity, and behavior, despite the fact that circulating glucocorticoids have a different profile.

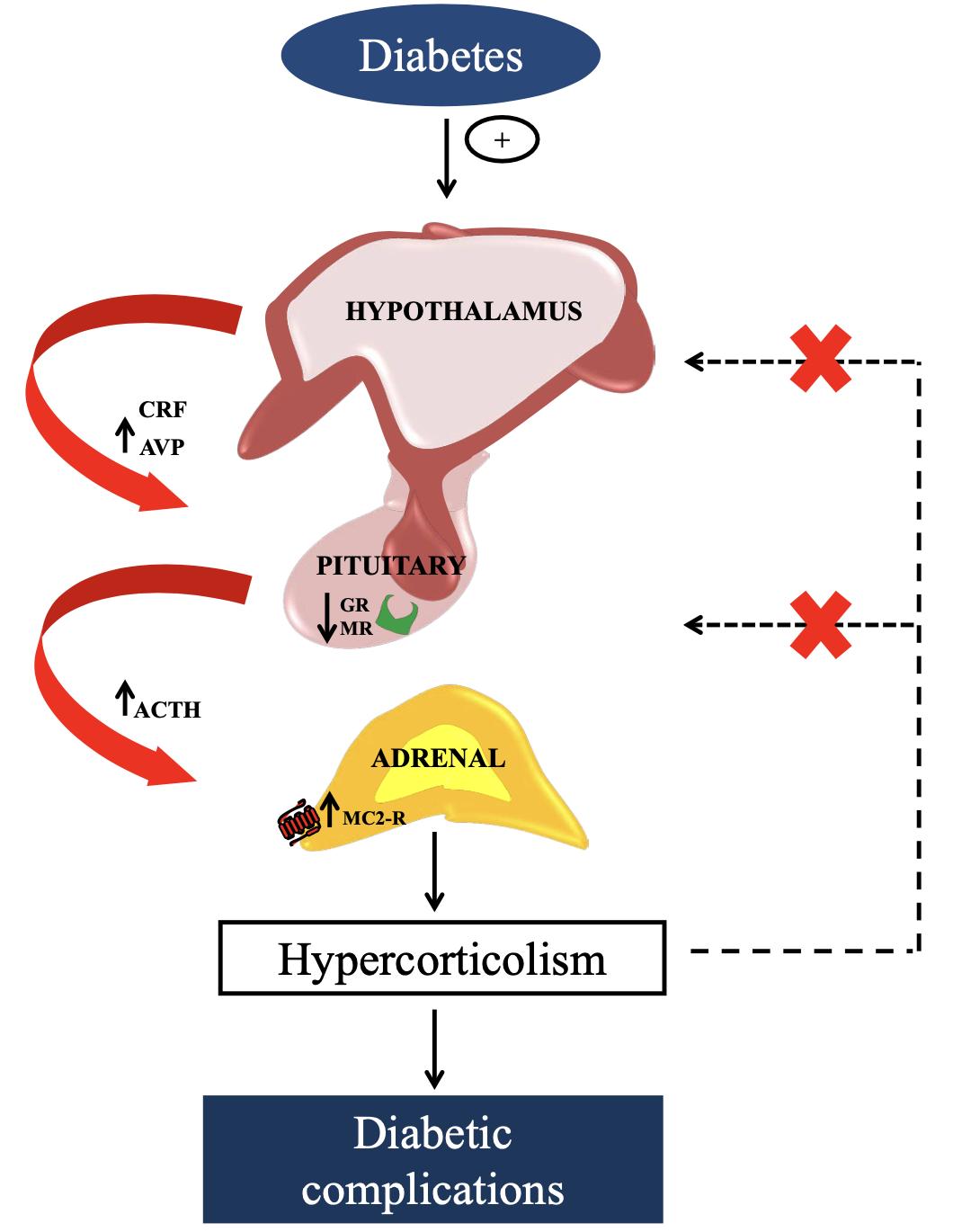

A rise in central drive and a decrease in glucocorticoid negative feedback sensitivity are linked to hyperactivity of the HPA axis in type 1 diabetic animal models. An increase in ACTH synthesis, elevated POMC expression by the hypothalamus, and elevated AVP levels are all outcomes of the dynamic alterations seen in these animals' pituitaries, adrenal glands, and hypothalamus. In addition, we demonstrated that the fasciculate zone of the adrenal glands had an increased expression of ACTH receptors (MC2R) in mice with alloxan-induced diabetes. After the dexamethasone suppression test, the glucocorticoid negative feedback sensitivity of the HPA axis decreased in rats with type 1 diabetes. Due to a decrease in glucocorticoid receptors (GR) and mineralocorticoid receptors (MR) in the pituitary, glucocorticoids are unable to exert their negative feedback on the HPA axis in alloxan-diabetic rats. Insulin treatment normalizes HPA axis activity by suppressing ACTH and glucocorticoid secretion, which is linked to decreased insulin levels in type 1 diabetes. This normalization may be due to an increase in GR mRNA levels in the pituitary and an improvement in glucocorticoid feedback at the corticotroph cells.

The mechanisms responsible for hyperactivity of HPA axis observed in type 1 diabetes. (Torres R C., et al., 2013)

References